Day 129 - Local Arts Funding

The next few text and sound pieces posted on TAAK´s website, of which this is one, will be subsidised by Netherlands based taxpayer money. Full disclaimer: as an artist I am also a taxpayer. Though the routes that money takes are not fully transparent to me, there shouldn’t be a misunderstanding as to whether I’m being paid by others. Worry not, I also pay.

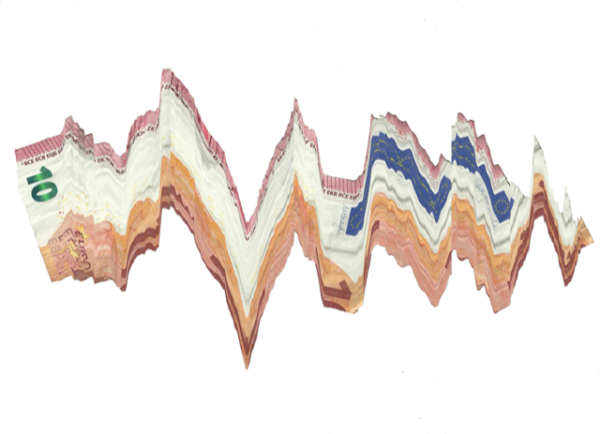

Right, so circling back, these next pieces are going to be mostly Amsterdam focused – and are supported by a grant which was offered through an application to an open call from the Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst (AFK). With that in mind, Amsterdam itself has always been a city of connections, a point of encounter from which multiple threads reach out. And even more so, it has recently committed itself to something which is called the “donuteconomie” – a la Kate Raworth´s Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, a model of functioning which takes into account, among others, moving the focus from infinite growth to thriving, considering how a city connects to others through its people and sourced materials, as well as how it can keep itself in sustainable balance – hitting that sweet spot for humanity in which there´s justice, equity and long term thinking which is not at odds with protecting the planet.

But making a move from a growth obsessed city to a balance mindful one is not a smooth transition. Even if one is to first pass through a complete stop, a reconsidering of priorities, which the COVID-19 pandemic represents. Old ways of thinking are hard to shake.

In March we, in the Amsterdam based artistic community, were confronted with an impasse. Our avenues of expression and our sources of funding would be temporarily stopped due to the fact that public space and institutions could no longer function as usual. Application times for funding would prove too long and ineffective. There would be a lack of income, but rents would continue, and while we managed to suspend the possibility to go out, we hadn´t yet achieved not eating. So as artists we needed funding to keep ourselves afloat, and we also might have experienced the dread of not knowing how our practices would continue in a world which was suspended. Therefore, on top of funding, we needed hope.

Enter – one of the devised solutions. So, at the beginning of the pandemic, the Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst (AFK), the municipal funding body in charge of supporting Amsterdam based artistic initiatives, put together a package of 300.000 Euros which was implemented with a speeded up application procedure called the “Snelloket”. The applications could count on a max of 5.000 Euros divided across their project needs (materials, honorarium, space etc.). This grant was intended to come to the aid of artists, but also imposed on them the obligation of reflecting through their projects on the coronavirus pandemic – be that in terms of topic, or format, which meant taking into account the distancing rules, the hygiene exceptions, as well as the number of people gathering in a space which was updated every two weeks by the government. But also, as one would imagine, they were to reflect, through their outcomes, on the philosophical, physical, aesthetic, conceptual (and so on) framework of the pandemic.

I applied and I received the grant. It’s interesting to state this support, since it frames the pieces I’m about to write as in a way commissioned, carrying within them a responsibility towards a funding body and maybe even an obligation in terms of what can be produced – as stated. Sure, everything and anything could be theoretically framed as corona influenced production, as it took place during 2020 and the global nature of the pandemic means it’s inescapable, but it makes one rather weary of their task and hyper aware of their creative limitations.

I believe it’s important to state this framing before moving on. And rather than just state it, it’s also worth diving into the way in which it was actually implemented (as far as time passed allows reflection), as well as which assumptions about the way artists work can be understood from it.

The AFK “Snelloket” was implemented starting on April 14th and was meant to work on a rolling basis. Artists would get to apply every Wednesday at 9am, the first 10 applications would be accepted, processed and approved or declined based on content, quality and feasibility, within 5 days of the application date. Each application would contain a project description, project budget, portfolio, and would have to be ready in a matter of days, given the short timeframe between the making public of the subsidy regulations and the deadline for applying.

The pressure to frame a coherent idea based on an ongoing situation which is unprecedented in human history, while, you know, making sure one doesn’t lose their mind, didn’t seem like a stretch for the funding body. Thus, it took for granted the expectation of the artists’ adaptability, which is pre-pandemic thinking and therefore nothing new. The implication that one has to jump through bureaucratic hoops while worrying about making rent is by now basically part and parcel with the artistic profession.

These automatic ways of thinking don't yet fall in line with the above mentioned “donuteconomie” mentality, in that they don´t take into account the conditions the applicants are subjected to – see: pandemic – but rather work to accelerate the precarity which was experienced by artists even in pre-pandemic times. I´ll go along and explain.

So applying for funding, where one would get to professionalize themselves, submit bureaucratically and squeeze themselves into conditions, ending up overworking and producing stellar results which would reach large and diverse audiences, is pretty much the norm for Amsterdam artists interacting with the Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst.

What was rather new, an added layer of complexity, was the assumption that there would be a limit on how many people could apply and that the limit would be set to 10 artists weekly. A challenge even in normal times, a downright proof of temporary insanity in corona times. This resulted in a first week of the AFK website crashing, hundreds of artists not being able to submit an application and overall frustration. Ever the adaptable institution, in the second week the AFK decided to change the application procedure and rather than accept only the first 10 applications, it allowed all applications that were submitted between 9am and 5pm on the day the online counter was open – hinting subtly to the fact that fund employees enjoy a Monday to Friday, 9 to 5 sort of job, in contrast to artistic flexibility. What those employees were overwhelmed to discover, is that the change they applied to the application procedure would open the floodgates and let in a few hundred applications that would force processing times to quadruple, and the budget to be exhausted in the second week.

Rest in peace, Snelloket!

What was intended as a speedy and efficient procedure and which most likely was created with the aim of offering an occupation to artists, a source of income and visibility, turned into a variation on “The Hunger Games”, in a moment in time in which what was needed was support.

The process was repeated in other cities. In Rotterdam for example, the allocated budget was distributed in the same manner, but rather than adjust the procedure due to an abundance of applications, CBK Rotterdam – the responsible institution – decided to keep only ten applications from one week to the next, turning the ability to quickly refresh ones browser page into an artistic achievement in and of itself.

Den Haag, instead, chose for a more humane approach in terms of what it allocated. Stroom – the organization in charge among others for artists grants in the city – turned 30 in 2020. It decided to celebrate by dedicating its festivities budget to the local artists instead in 3,030 Euro instalments that were meant, once again, to projects tackling the impact of corona. The procedure had no weekly deadline, but an end date (July 1st) and then it took into account the date by which the budget would be exhausted.

I received the funding in Amsterdam three weeks after successfully applying and, given the delay, almost at the end of the partial lockdown. I received the funding while exhausted, stretched too thin, having juggled the shot of adrenalin in the initial COVID weeks, moved through exaltation and despair – and once I received the budget I also suffered an immense blockage. Too tired to react I puzzled instead at the process I had put myself through and wondered – can this be bettered?

And that´s when I decided to look into the “donuteconomie” model that Kate Raworth advocates and superimpose it on what funding for artists currently is, and dream of what it could be instead.

So, in the case of the AFK, what have we?

First, we have artists that need basic security in terms of the current moment. Since during the pandemic, rent is not suspended and groceries aren´t either, they need to know they can count on funding which tackles these core elements. This does not have to be “project funding”, but should be instead thought of as a basic income.

Then, we also have an idea of continuing individual and collective practice and allowing that to thrive – but one needs to think in terms of what is urgent when a crisis comes up, not in terms of accelerating competition. So in a situation in which the aim is to support the city´s artistic life, you can´t go ahead and implement a procedure which forces hundreds of artists to compete to be seen by a funding body that can only manage to see 10. How about, instead, not making it a competition at all, but ensure you can distribute the funding, as equally as possible to as many as can apply, on a one-off instance – which doesn´t need to guarantee more production, but simply to ensure your artists are taken care of in a moment of crisis?

Third, when passing through a traumatic event: offer guidance, offer counseling, offer resilience training, offer a humane approach to how you treat your artists. And through that, consider the humanity of both sides of the process – artists and funding institution employees. Rather than turning AFK representatives into the recipients of hundreds of budget proposals, project descriptions and CV´s, cutting all phone contact between artists and funding institution, and turning the application process into an impersonal one, establish lines of communication and cut bureaucratic expectations.

And forth, and final, give up on addressing the artist as the ever more entrepreneurial self, even in times of pandemic. Give up on trying to make artists instrumentalise a global emergency into material for their art and into a guarantor of visibility. Allow them instead to focus on what they care for at that time in their practices. This may or may not be something that one can fit into a pandemic retrospective exhibition.

But how about allowing the artists to decide that instead?

Our New Normal is made possible in part by AFK (Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst).

Announcing: Our New Normal

Announcing: Our New Normal